The Cambridge Companion to the Musical | Ed. William A Everett and Paul R. Laird

Chapter Outline

Preface | William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird

xvi: “The possibility of such experience [entertainment] is almost an unwritten contract between the show’s presenters and their audience. What we offer here is a history of that contract’s constant renewal and reinvention.”

Part I: Adaptations and transformations: before 1940

Ch1: American musical theatre before the twentieth century | Katherine K. Preston

Argument: The theatre traditions of the 18th and 19th centuries were largely musical, to such an extent that it is impossible to view the repertory of “theatre” and “musical theatre” as separate. Theatrical productions in this time catered to catholic tastes, with variety and turnover equal to that of the modern multiplex; on offer was opera, melodrama, minstrelsy, pantomime, burlesque, spectacle, extravaganza, operetta, and revue. The (music) theatre was also a fundamental part of American life, permeating popular music, dances, and music played at home. Modern scholars of musical theatre can learn from the cross-fertilization of forms that took place during the 18th and 19th centuries, lending to an integrated—rather than taxonomical—view of musical theatre history.

- 18th Century

- Pre-revolution dominated by itinerant or “strolling” companies. Post-revolution saw the rise of permanent theatres. All repertory relied heavily on music; ‘theatre’ and ‘musical theatre’ were essentially synonymous.” (4-7)

- 1800-1840

- Emergent star system, where a visiting star would perform at different theatres in turn. This period dominated by stock productions at local theatres, with material largely derived from London. (7-8)

- ★ Melodrama emerges in its original form: “the use in drama of short musical passages to heighten emotional affect, either in alternation with or underlying spoken dialogue.” (8)

- Vocal stars bring greater appetite for Italian operatic music. (10)

- 1840-1865

- Stock companies expand to accommodate circuit performer: minstrels, operas, acrobats, dancers, pantomimists (11)

- Melodrama gains meaning of a particular kind of drama—good beats evil (12)

- Minstrelsy emerges as a fundamentally musical variety show (13-14). Later, black minstrel troupes mark influx of African-American performers. (22)

- Pantomime emerges, feeds into spectacle and extravaganza (14)

- Burlesque gains popularity as a satirical production with music (15)

- 1865-1900

- Theatrical syndicate/managerial offices emerge (18)

- ★ The Black Crook (1866) cited as first real precursor to the musical: extravaganza with melodrama, ballet, spectacular scenery, costumes, tech theatre transformations (19)

- Opera seen as increasingly exclusive (22-23). Opera-bouffes popular until translated to English, seen as offensive (24). Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore marks a turning point in MT history: inoffensive, light, humorous, satirical, melodic (25).

- Vaudeville and revue emerge at this point (26-27)

Ch2: Birth pangs, growing pains and sibling rivalry: musical theatre in New York, 1900-1920 | Orly Leah Krasner

Precis: Krasner does not offer an argument so much as a synopsis of the movers and shakers of the pre-musical stage from 1900-1920. Nonetheless, her history is threaded with connections to modern musical theatre practices, suggesting a sort of continuity of form and practices over the distance of a century. These include, but are not limited to, revues, spectacle, entertainment retail, transnational circulation, and vernacular idioms.

- George M. Cohan and Little Johnny Jones (1904): often credited as the first musical, Cohan’s vaudevillian roots brought street-wise humor and vernacular lyrics to a stage otherwise populated with quasi-Gilbert-and-Sullivan overblown imagery. (30)

- Victor Herbert caters to stylistic variety, but also champions coherency, leading to conflicts with stars who traditionally interpolate songs into shows. (31-33)

- Reginald de Koven attempts to elevate craftmanship and audience taste. (34-35)

- ★ “While Cohan’s shows were establishing a taste for vigorous Americana… de Koven and Herbert were making their first tenuous moves towards sentimental romances set in European locales” (35)

- The Merry Widow is a sensational Austrian import that spurs itself as a marketing gimmick—forerunner of entertainment retail (37)

- Operetta’s popularity: appeals to recent European immigrants, Americans looking to their roots, upwardly mobile who want “sophisticated” forms but cannot understand opera, middle class who respond to talent (40)

- ★ Two trends: symbiotic relationship between music and story, and effacing scenario for scenery

- Ziegfled Follies (41-42)… “ethnic humor endemic to the genre” (42)

- Berlin and Kern begin as interpolators, grow from there (43-45)

Ch3: Romance, nostalgia, and nevermore: American and British operetta in the 1920s | William A. Everett

Argument: While operetta in the Gilded Age functioned as a vehicle for escapist romanticism, the lasting legacy and appeal of the form is in the sense of nevermore—nostalgia for an older time. Though operetta grew out of Central European roots, it became Americanized through non-Ruritania settings that were remote either through the distance of time or space.

- Traditions of operettas set in Ruritania (fictional Central Europe) cannot hold after WWI–>escapist Gilded Age fantasies in American/French historical settings (47-48)

- American operetta rooted in escapist romanticism—remoteness in either time or place (55)

- Friml (Czech) and Romberg (Hungarian) explore the Canadian Rockies / Native Americans (Rose-Marie) and Ruritania (The Student Prince)

- Future shows explored North Africa, Civil War Maryland, 18th century Louisiana, Japan, Arizona, Caribbean islands, historic France

- Central European models with verse-refrain form of Tin Pan Alley (54)

- NB: Hammerstein is active with these collaborators.

- American operetta falls with the Great Depression, due to taste for humor and prohibitive costs. Maintains sense of old-fashionedness and nevermore (56)

- British operetta avoids Ruritania, post WWI. Lots of American imports. (57)

- Hollywood operettas repurpose songs/plot to deliver star-power of Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, and to privilege the nevermore nostalgia (60)

- Operetta’s legacy: source for pastiche/parody, dramatic model for MT (61-62)

Ch4: Images of African Americans: African-American musical theatre, Show Boat and Porgy and Bess | John Graziano

Argument: “From its beginnings after emancipation, African-American musical theatre pursued two contradictory goals—to entertain and to enlighten.” (76) Graziano traces, here, African-American performance practice from 1865 to 1935, the end of the Civil War to the middle of the Depression. The history he traces is essentially a sine curve, oscillating from performances that lean on stereotypes and those that present a “realistic” view of the African-American experience.

- Stereotyped productions: minstrels, Octoroons, Trip to Coontown, Shuffle Along

- Realistic productions: Before and After the War, Urlina, Clorindy, Sons of Ham

- These shows represent educated black middle class, privilege Africanness

- Clorindy the first black show on Broadway, featuring ragtime syncopated rhythms authentically performed by black people. (68) Rhythms still associated with lower-class immorality.

- Show Boat addresses passing and miscegenation (73); Hammerstein offers “serious and sympathetic portrayal of African Americans” (74).

- ★ “Show Boat‘s serious treatment of social issues was not matched until West Side Story” (75). Tall claim. Also—Graziano never notes the advent of the actual musical form.

Ch5: The melody (and the words) linger on: American musical comedies of the 1920s and 1930s | Geoffrey Block

Precis: Block’s chapter may be divided into three parts: first, a comparative overview of the context and thematic content of American musical theatre in the 1920’s and 30’s; second, an examination of the artistic practices of the major artists from that period; and third, a survey of the legacy left by the musicals of this era.

- Context: While the indulgent, Jazz Age culture of the 1920’s favored topical themes like Cinderella stories, bootlegging, and the Lindbergh flight, the darker mood of the 1930’s Depression era favored political themes. (78-82)

- Musical comedies of both decades develops the American style of vernacularly inflected rhythms and melody—ragtime, blues, jazz, swing (83-84)

- Artists: From Kern (1885) to Rodgers (1902), these men share similar upbringings: born in NYC, sons of recent Jewish immigrants, with formal music educations (86). Berlin (Russian immigrant) and Porter (Protestant Hoosier) are exceptions.

- All of them use the 32-bar song, largely AABA (87)

- All of them drawn to Hollywood for $$ during the depression (86)

- ★ Idiosyncrasies: Gershwin: pentatonic melodies, blue notes ,repeated notes with changing harmony on each repetition; Porter: juxtaposition of major and minor modes; Rodgers: simple scale, surprising notes at ends of phrases, waltzes. | Hart: bittersweet/unrequited love; Porter: direct approach to love; Ira: moment of falling in love (87-88)

- Music comes first before lyrics (88), though title comes first before music

- Three legacies: revivals, films and reconstructions, songs

- Revivals tend to update shows for modern integrated musical sensibilities, often raiding a composer’s oeuvre (92)

- Films distort the original similarly (92)

- Restorations aim to recreate the original conception of a show, often at the expense of the Broadway reality—ie: what the artists intended, not what actually played on stage (96)

- Some songs survive independent of context. (Think “Summertime”)

Part II: Maturations and formulations: 1940 to 1970

Ch6: ‘We said we wouldn’t look back’: British musical theatre, 1935-1960 | John Snelson

Argument: “World War II interrupted the development of British musical theatre and led to a post-war dichotomy between the need to take up again and develop the interrupted past as an assertion of continuity and the need to embrace change in a world that could not be the same again” (118). British musical theatre in the post-war period caters to a particular sort of nationalism (and old-fashionedness) that accounts for its success within its particular context, but also its failure to circulate and to endure to today. This period of British musical theatre is largely forgotten, but establishes the British plotline of retrospection and anticipates the megamusical.

- 1935-1939: Ivor Novello, a composer/playwright/actor, pioneers the musical of excess—emotive in music, romantically idealized, visually impactful (103). A forerunner to Andrew Lloyd Webber. Noel Coward is remembered through individual songs, but not a coherent repertoire.

- Wartime: High demand for entertainment to raise morale, but few new shows. (105)

- 1947 and the American invasion: Oklahoma! brings the escapist image of vigorous youth, Annie Get Your Gun brings energy/style (107)

- In this time, British success is Bless the Bride, a Victorian show with Gilbert and Sullivan idioms, where the music builds national identity (108)

- Also King’s Rhapsody, which deals with the very British idea of royalty (110)

- Generalized sentiment of American=new, British=old. The British agenda is impenetrable to outside audiences, and irrelevant today. (111)

- 1950s: Golden City imitates OK! on the South African frontier. Gay’s the Word takes up American confidence and energy. (113)

- British theatre perhaps limited by long-established culture of compliance and censorship. Only later do its writers become freer. (115)

- The Boy Friend and Salad Days appeal to Britishness: upper-class, Cambridge—light, inoffensive (115-16)

- Repertory becomes more serious / less restrained circa 1956 with Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be (class conflict), Grab Me a Gondola, Expresso Bongo (117)

Ch7: The coming of the musical play: Rodgers and Hammerstein | Ann Sears

Argument: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! was a landmark in American musical theatre history, inaugurating a partnership that dominated the genre from the 1940s and 50s. Their trademark formula included integration (book, lyrics, music), direct approach to social/moral issues, simple often sentimental language, use of reprise, atypical love story, important child characters, strong women, narrative use of lance, the almost-love song, and depiction of environment through lyric/music/design (see: 125, 127, 134).

- New things from this chapter:

- Just before OK!, Hammerstein revitalized his career with a Bizet adaptation set in the south: Carmen Jones (122)

- OK! turns the operatic convention of pairs of of lovers to pairs of love triangles (124)

- R+H worked in the film industry together, continuing to use song for characterization (127)

- R+H after Carousel alternated writing and producing other work (129)

- Allegro “may have been the first concept musical” (130)

- South Pacific had two serious couples, hence Bloody Mary and Billis (131)

- 131-132: Focus on children as pivotal to plot

Ch8: The successors of Rodgers and Hammerstein from the 1940s to the 1960s | Thomas L. Riis and Ann Sears with William A. Everett

Precis: This chapter reads like a blow-by-blow overview of musicals in the 1940s-60s, with attendant commentary on what each show owes to the Rodgers and Hammerstein formula. That formula is articulated as bookends to the chapter: historic subject matter, earnestness, nostalgia, integration, strong book, and integrity with popular appeal. At times, this history seems to depart from the R+H analysis, and simply recapitulates production history. It is not clear what qualifies a show for inclusion in this chapter—Kander and Ebb’s distinctly non-R+H Cabaret is included, for example, but West Side Story is mentioned only in passing.

- While some shows explore romance and fantasy, many center on American experiences at home and abroad and around military life (140), after OK!

- Arlen: Bloomer Girl (1944), St. Louis Woman (1946), House of Flowers (1954): historic settings (140), serious subject matter (141)

- Berlin: Annie Get Your Gun (1946), Miss Liberty (1949), Call Me Madam (1950): sometimes historical, not integrated (141, 146)

- Styne: High Button Shoes (1947), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949), Gypsy (1959), Funny Girl (1964) – show-business razzle-dazzle as trademark, non-R+H (142-43), serious subject matter (153), recent historical figures (158)

- Lerner and Loewe: Brigadoon (1947), My Fair Lady (1956), Camelot (1960) as heirs apparent to R+H: well-written book, exotic locales, operetta-influenced music, idiomatic language (143, 149) + allusion to IRL (Arthur=JFK) (156)

- Hammerstein was offered MFL but could not resolve the non-love story (148)

- Kiss Me, Kate (1948) – Porter: realistic, integrated + wit (145)

- George Abbott as show doctor (146)

- Loesser: Guys and Dolls (1950), – collaboration, romance and comedy coexisting in the same character (147)

- ★ Lehman Engel (R+H conductor): great musicals begin with great books (149)

- Strouse and Adams: Bye Bye Birdie (1960), Golden Boy (1964), Annie (1977): substantial social issues (154-55)

- 1960: R+H ends, Lerner and Loewe ends: close a chapter of MT history (157)

- Bock: Fiddler on the Roof (1964): genuine experience on stage (159)

- Herman: Hello, Dolly! (1964), Mame (1966) smashes as spectacle, no mention of R+H (160)

- Man of La Mancha: ditto.

Argument: In the coda to this chapter, Everett traces the remnants of 1940s-60s musicals in recordings and revivals. Of note are not only cast recordings, but also artist recordings of a larger MT repertory (163)—think Bernadette singing all of Sondheim. Interesting case studies covered here include the animated King and I (1966), which makes the plot a melodrama, Robbins’ Cradle Will Rock (1999), and the color-blind Cinderella (1997). The most salient point here is that these recordings, sonic, filmic, or otherwise, is how new generations access these shows.

Ch9: Musical sophistication on Broadway: Kurt Weill and Leonard Bernstein | bruce d. mcclung and Paul R. Laird

Argument: In a counterpoint to chapter 8, this chapter argues that while most American musicals post-OK! followed the Rodgers and Hammerstein model, Kurt Weill and Leonard Bernstein went against the grain and continued to produce sophisticated scores in a variety of styles. The chapter traces both of their careers, and suggests that Bernstein is Weill’s heir.

- Both composers composed in cultivated forms and vernacular genres, and capitalized on technology (radio, tv) to reach broader audiences (169).

- Weill constantly switches forms: every new work is a new model (173)

- Weill’s Johnny Johnson (1936) features a tightly written score and inaugurates his practice of leitmotif (169). Knickerbocker Holiday (1938) veers closer to operetta (169). (Weill was also his own orchestrator.) Lady in the Dark (1941) used music to advance psychological progress, and established the practice of advance sales on Broadway (170).

- Chapter calls Lady a “mega-musical” (170)

- Street Scene (1947) attempts American opera with blended word/song/music and a “melting pot” of musical styles (171-72). Love Life: A Vaudeville (1948) adumbrates the concept musical (172).

- Last show is Lost in the Stars (1949), adapting Cry, The Beloved Country.

- Weill’s Johnny Johnson (1936) features a tightly written score and inaugurates his practice of leitmotif (169). Knickerbocker Holiday (1938) veers closer to operetta (169). (Weill was also his own orchestrator.) Lady in the Dark (1941) used music to advance psychological progress, and established the practice of advance sales on Broadway (170).

- Bernstein begins as a conductor, and a Hollywood presence. Champions thoroughly integrated score.

- On the Town (1944) brings him to Broadway by way of modern dance (174). Every dance advances the plot.

- Wonderful Town (1953) is more in the vein of musical comedy (175).

- Candide (1956) is a wonderful pastiche of musical styles, but suffered from lack of central concept between collaborators (176-77).

- West Side Story (1957) integrated everything, and used music to separate social groups and suggest social relationships (177).

- 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (1976), his last work, suffers from a bad book (178).

Part III: Evolutions and integrations: after 1970

★ Ch10: Stephen Sondheim and the musical of the outsider | Jim Lovensheimer

Argument: Sondheim shows are characterized by their focus on the outsider—a figure largely left out of the American musical theatre tradition. (Think: Curly and Laurey rather than Jud.) Sondheim scores exhibit multiple musical voices in pursuit of a singular voice: that of character delineation. Two key strategies Sondheim uses to advance this aim are motives and pastiche. Lovensheimer traces these three threads—outsiderness, motives, and pastiche—through Sondheim’s oeuvre from West Side Story to Assassins.

- Prior to Sondheim, significant focus on the figure of the outsider fell to his mentor, Hammerstein: Show Boat, Carmen Jones, Oklahoma!, Carousel (181)

- Sondheim’s outsiders dream of escaping reality: Tony/Maria dream ballet, Bobby’s epiphanies, George’s encounter with Dot (182-83)

- Swayne: Sondheim exploits “range of musical voices in pursuit of his singular voice: the voice of character delineation” (183).

- Company: “Bobby” motif appears in songs that relate Bobby to couples; does not appear in commentary songs, Bobby solos, or girlfriend songs (184)

- Anyone Can Whistle: musical comedy idiom for mayor (185)

- Follies: Gershwin-like “Losing My Mind,” vaudeville “Blues,” Porter/Weill-esque “Lucy and Jenny,” Berlin/Gershwin-like “Live, Laugh, Love” (186)

- A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd: all characters are outsiders, dispossessed (188)

- Form makes audience outsiders—concept musical (Company, Follies), or movement through time (Merrily) (188)

- ★ Narrator elimination (Into the Woods, Assassins) enhances the power of outsiders (189)

- 189-195: Close reading of two Assassins numbers that take popular musical idioms and give them to the losers/loners/outsiders

Ch11: Choreographers, directors, and the fully integrated musical | Paul R. Laird

Argument: The assumptive argument in this chapter is that the “fully integrated musical” comprises one that integrates dance into its plot/characterization/setting. Laird traces the careers and innovations of seminal choreographer-/directors, from Agnes de Mille to Jerome Robbins to Bob Fosse to Michael Bennett, with several more besides.

- George Abbott: Directed On Your Toes, with significant use of dance. Abbott taught Robbins, Fosse, and Prince. (199)

- Agnes de Mille: OK!, One Touch of Venus, Bloomer Girl, Brigadoon, Allegro. Use of highbrow ballet and counterpoint for visual appeal (199-200).

- Jerome Robbins: Comes out of ballet with Bernstein and On the Town. Develops his career with High Button Shoes, Call Me Madam, Uncle Tom’s Cabin dance in The King and I. Co-director in The Pajama Game. Full director in West Side Story. Values method acting, divided the cast in two. With Gypsy, less of dance but still skillful staging. Fiddler brings dramaturgically crafted choreography. (200-203)

- Bob Fosse: Came from ballroom and ethnic dances. The Pajama Game, Damn Yankees, Redhead, Sweet Charity. Often choreographed for Gwen Verdon, his third wife. Noted for parodic suggestiveness. (203-206)

- Gower Champion and Hello, Dolly! benefits from staging and choreo. (206)

- Hal Prince not a choreographer, but continues to advance dance integration. (206)

- Michael Bennett begins as a dancer. Co-director of Follies. [The famous story of A Chorus Line: workshopping, pre-cast, lack of intermission, rapid pace.] “Much of the show’s action seems to occur in real time.” (206-210)

- Tommy Tune: mines history of American entertainment –> choreo pastiche (211)

Ch12: Distant cousin or fraternal twin? Analytical approaches to the film musical | Graham Wood

Argument: The film musical as distinct from the screen musical can be approached through three areas of investigation: technology (sound, color, camera); genre (adaptation, OC, biopic); and style (musical, visual, and dance). All movie musicals are in some way self-reflexive, quoting or alluding to its own history—the history of musical theatre, the entertainment industry, or the process of making musicals. This chapter outlines approaches, considerations, and vocabularies that further analysis of the movie musical.

- Technology:

- The advent of lip-synching frees the camera from the inflexibility of a soundproof booth. Microphone technology more generally will affect the vocal techniques used by singers/actors (see: Song)

- Genre

- ★ Block: difference between between theatrical truth and literal truth: what is dramatically convincing in the theatre vs. what is convincing in film (216)

- e.g: switch of “Cool” and “Gee Officer Krupke” from the stage to screen

- Camera allows the musical to access a larger world (think: SoM Austria) (216)

- Categories: adaptation, original film, biopic

- Adaptations from the stage often interpolate new songs or songs the studio already owns–>how does this affect music narrative? (218)

- Biopics include films not always understood as musicals, like the Elvis or Beatles movies. Biopics foreground technology (think: SitR) (219)

- ★ Block: difference between between theatrical truth and literal truth: what is dramatically convincing in the theatre vs. what is convincing in film (216)

- Visual Style

- “The silver screen contains a fundamental dualism between realism and fantasy” (220): because of actual news, there is an expectation of realism that must be overcome: largest difficulty is in making a convincing transition from dialogue to song

- Roving camera in Busby Berkeley films elevates film to fantasy (221)

- Animated musicals use contrasting styles to effect fantasy (221)

- “Pink Elephants on Parade” allows fantasy to leak into reality, whereupon Dumbo can fly

- Visual symbols also add to the impact, sense of forward motion (222)

- Musical Style

- Song: provides narrative thrust, insight into character psyche, or reflection on an external object (223) AABA, etc

- Diegesis: movie musicals disproportionately include diegetic performance, allowing underscoring to bleed into diegesis (224)

- Transition: Dialogue bleeds into lyric, underscoring bleeds into accompaniment. Weird approach to transition is rhyming dialogue (225)

- Transitions out of songs: applause, cut to view from the wings, black-out

- Wood points to Disney as a site of further investigation (226)

- Song migration: songs appear in more than one movie, eg: Blue Skies (227)

- ★ Singing and lyrics: microphones allow intimate singing styles, and lyrics to end with short vowels/clipped consonants rather than long vowels (227)

- Dance Style: varies hugely

Ch13: From Hair to Rent: is ‘rock’ a four-letter word on Broadway? | Scott Warfield

Argument: This chapter considers the rock musical, beginning with a reflection on its loosely defined taxonomy. From there, it takes a tour through the musicals inflected with “rock,” and arrives at its defining traits. Not only do rock musicals employ contemporary music styles, but they also appeal to issues that interest younger generations—war, identity, spirituality, growing up. In its infancy, the rebellious “rock” musical is that form for the disenfranchised—today, it is no longer that.

- “Rock musical” used loosely to describe any production with pop inflection (231)

- Four categories of rock: (1) identified as such by creators, (2) began as concept albums marketed to rock audiences, (3) used rock styles but not ID’d as such, (4) emulate early styles of rock ‘n’ roll. (232)

- Bye Bye Birdie (1960) is first to use rock. However, economic conservatism of Broadway prevents its return for seven years. (233)

- ★ The Case of Hair (233-236)

- Grows out of workshop production. Narrative of anti-authority.

- Avante-garde techniques involve audience. No fourth wall.

- Rock style evident in percussion, but verse-chorus format of Broadway.

- Remarkably inexpensive—less than a third of typical $50k.

- Emulators of Hair largely fail

- ★ Promises, Promises innovates with a miked orchestra/back-up singers. Audiences come to expect performances to match commercial recording sound. (236)

- ★ Characteristics: guitar/drum ensemble with contemporary music style, “outsider genre” carries issues important to young people (war, spirituality, identity, growing up), grow out of Off-Broadway (239)

- Key to successful rock musical is still integration (240). Rent, Mamma Mia!, Hedwig

- “Linguistic imprecision… confirms the desires of producers to exploit the popularity of rock, while simultaneously suppressing its rebellious spirit and most extreme sounds” (242) –> consider, though, that rock is respectable by late 1980s. New “disenfranchised” genre is hip-hop. (244)

- 2002 piece is delightfully outdated in claiming the absence of rap musicals.

Ch14: The megamusical and beyond: the creation, internationalisation and impact | Paul Prece and William A. Everett

Precis: This chapter may be broadly divided into two sections: first an analysis of what the megamusical form owes to nineteenth-century French grand opera, carried by Schoenberg-Boublil; then an in-depth analysis of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s oeuvre and themes that interlink his shows.

- Nineteenth-century French Grand Opera (246-48)

- A “grandiose” medium combining music, drama, dance, lavish costume, lavish sets, special effects. Set against war backgrounds. Addresses social injustice.

- These strains are reproduced in Les Miz, Miss Saigon, Martin Guerre

- Key players: Cameron Mackintosh, Claude-Michel Schoenberg, Alain Boublil

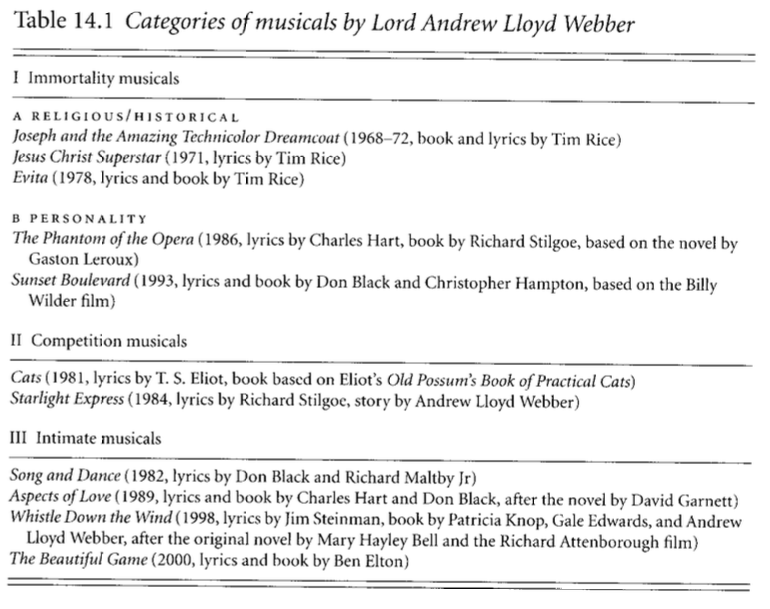

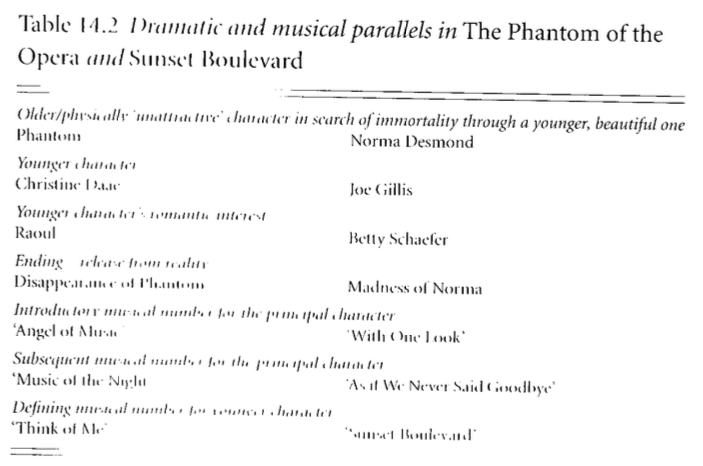

- Andrew Lloyd Webber: focus on redemption. Two charts:

- Amusingly, the authors also note that Phantom and Sunset prominently feature both a staircase and monkey.